August 6, 2025

How to spot and prevent girdling branches

The selection of branch arrangement is the most challenging pruning concept to understand. It is easy to understand pruning for clearance over a building, or to remove deadwood, but unlike those more common prunes, structural pruning and selecting branch arrangement is difficult to sum up with simple metrics like 6 feet of building clearance or removing all deadwood over 1” diameter. Instead, we mimic the branch arrangements of the healthiest trees that grow in the wild to arrive at a few guidelines for selecting permanent branches or “scaffold branches”.

First let’s start with the International Society of Arboriculture (ISA). “Step four [of a structural prune] is to select and establish scaffold branches. These branches should be selected for good attachment, appropriate size, and desirable spacing in relation to other branches.” Arborists Certification Study Guide, 2010.

To break that down:

- Good attachment means U-shaped branch junctions with no included bark.

- Appropriate size means a branch-to-trunk diameter ratio of no more than 1:2, and a branch length that stays within the tree’s natural canopy outline.

- Desirable spacing means branches should be 12–18 inches apart vertically, and staggered—not directly opposite each other.

But why follow these guidelines? What issues do they actually prevent?

Without a clear picture of the why, it can be difficult to justify making significant cuts to what seems like a perfectly healthy tree. That’s where I hope to add value—by offering a closer look at a particular structural issue that I've observed often in Vermont: girdling branches.

What are girdling branches?

Girdling branches occur when multiple branches encircle the leader of the tree and outcompete it by taking over its water and nutrient supply.

Preventing this outcome, in my opinion, is the top priority when selecting scaffold branches. After all, it is a threat to the central leader that is the most important part of the tree’s structure.

Girdling branches strangle the parent stem they grow from. My hypothesis is that the strangling mechanism here, is the secondary growth, or thickening process, of the branches. In time, circling branches coming from all sides of the trunk can thicken to the point that the branch collar of two or more limbs overlap, effectively girdling the main stem.

How girdling happens

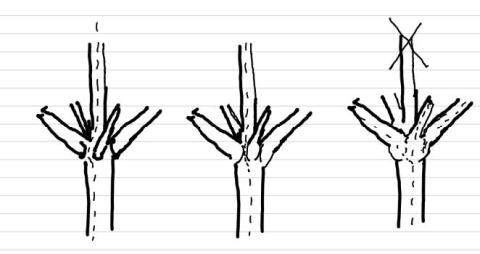

Diagram 1: girdling branch development

Once the sapwood conduit is redirected to the girdling branches they can then quickly outcompete the leader.

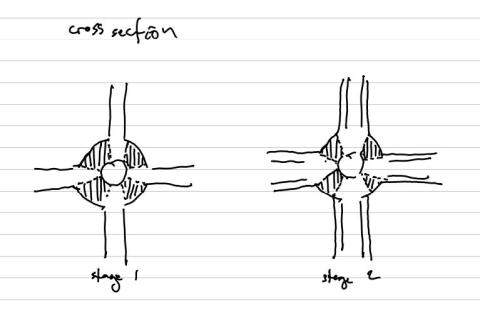

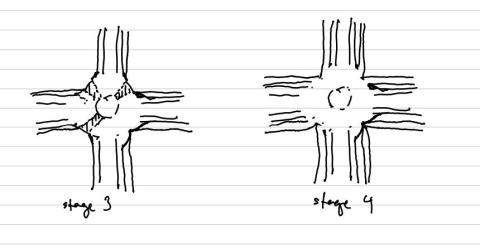

Diagram 2: hypothetical cross section of girdling branches developing over time.

Diagram 2: Continued

What you can do

Ideally stage 1 is the time to correct the girdling effect before it causes any damage. A small cut is always less harmful to the tree than a larger one. Simply reduce, or thin one or more of the circling branches. At this stage this branch arrangement really can’t be considered a defect, merely a warning sign. Stage 2 is still a perfectly good time to take action. You’ll need to decide whether to remove one or more of the girdling branches with thinning cuts, and/or reduce one or more of the culprits with small reduction cuts to stunt the rate of their thickening while allowing the parent stem to grow vigorously.

Pruning choices change significantly in stage 3, when two of the circling branches have thickened to the point of touching each other. This will likely now be influencing the growth rate and branching pattern of the main stem, the beginning of defect territory. An arborist might choose to prune the stage 3 tree a few different ways:

- Give up on the previous central leader, subordinate it, and choose one of the side branches to become the dominant stem.

- Remove one of the two circling branches that have connected to each other with a thinning cut in hopes the trunk will compartmentalize and maintain connectivity on that side.

- Slow down all the circling branches with significant reduction cuts, larger diameter cuts reserved for the larger branches. This puts you in the position to put sizable holes in the canopy of a tree, trading off the short-term aesthetics for long term health. Which stem to choose will be a judgment call that varies from tree to tree due to desired lean, surrounding targets, attachment quality and other signs of tree structural stability that are observed at the time.

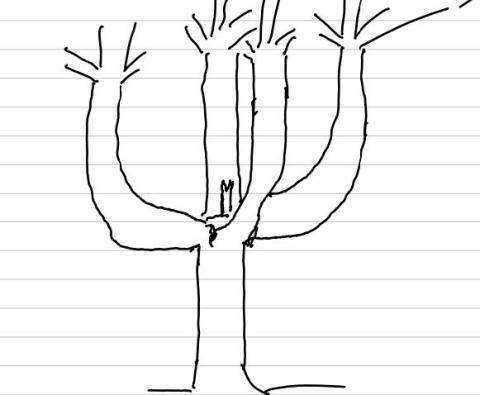

At stage 4, it's too late to save the original leader. By now it is probably much smaller than the side branches and probably has much more deadwood and less foliage than they do. At this point, an arborist may as well remove that leader entirely to allow the sides to take over. Once stage 4 is reached, we effectively now have 4 codominant stems.

Once this defect is fully developed, none of the stems are vertical enough to take on dominance, so the structure will need to be assessed for next steps. These stems will likely also be centered on a point of rot or weak attachment as well as exhibiting outward lean: an unstable combination. So, you may now consider cabling the tree or pruning to reduce weight and windsail on all the stems just to prevent major failures.

Which trees are most susceptible?

Conifers, especially spruces and firs that have a uniform upright shape, almost never fall prey to girdling branches. They seem to be better at resisting this since limbs remain small in comparison to the parent trunk. This is a common problem that occurs to varying degrees in hardwood trees especially opposite branching ones like maples. The three trees I recommend monitoring closely and pruning proactively to correct this problem are maples, oaks and apples, especially B+B nursery stock.

Oaks are not opposite branching trees, and rather than four co-dominant stems resulting from girdling branches, they may develop three codominant stems instead. When oak branches are close together vertically along the trunk, they can form a girdling branch situation that is staggered. A whorl of branches below may cut off connectivity on one side of the trunk, while the next whorl of branches cuts off the other side of the leader, causing a very similar problem.

The single worst species I know of for this defect is the Norway maple. The unstable structure caused by girdling branches may be their most common growth form, making healthy tree structure something of a rarity in the species.

Final thoughts

I hope this article was helpful in identifying and treating girdling branches before they begin. My real hope is that the message reaches professional arborists, who might find the chance to address girdling branches when they are encountered aloft, outside the view of the client. Keeping an eye out especially for places where two or more branch collars have already joined, or a slight lessening of vigor in the central leader can be traced down to overcrowded branch layers below.

Like any pruning guideline, this information needs to be applied in context. There is always a degree of artistry, interpretation, and opinion in applying pruning concepts. Though this is a pattern that can contribute to poor tree structure, it shouldn’t be treated as the end of the world or a definite reason to remove a tree entirely. Many times, when the beginnings of girdling branches are evident, the context may lead you to believe it will never develop into a problem.

This article represents my own observations and reasoning. I encourage comments and discussion on this topic so we can all continuously learn. If you have seen this phenomenon, and have other solutions for it, or thoughts about it, or if you have another name for it, I’d love to hear from you at adam.mccullough@vermont.gov.