January 8, 2025

This article represents the professional opinion of VT UCF’s Urban Forester but does not constitute an official stance of the Dept. of Forests, Parks & Recreation. Property owners with questions about how to manage a tree should consult a professional arborist for a detailed and site-specific recommendation.

I read a study recently that found that individuals with greater levels of training in tree risk assessment consistently prescribe fewer tree removals, and more monitoring than individuals who lack such training. (Klein et. al 2023.) Even professional arborists who are fully qualified to advise customers about their best interests in tree care prescribe more take downs than similar professionals who have received specialized risk assessment training. This study shows that the more you learn about tree risk, the more comfortable you become designating trees as safe.

I have lived through this progression of learning myself, starting as a Surface Dweller, sorry, a non-arborist, at which point I didn’t even know what to look for when assessing a tree’s potential risk rating. Later, becoming an International Society of Arboriculture (ISA) Certified Arborist made me much more aware of tree defects, the ways that tree parts fail, and the mechanics of a tree. I even correctly predicted multiple tree failures during this time, showing a huge leap in understanding compared to my pre-arborist days. Now I walk in the shoes of a Tree Risk Assessment Qualification (TRAQ) Certified Arborist. This training aligns the assessment of tree risk with risk assessments used in other industries and provides guidelines and methods that clarify tree risk, while also admitting an honest degree of uncertainty. After going through this progression of training, I see three key concepts that I have learned to enhance my accuracy and professionalism in Tree Risk Assessment.

Vermont is home to 250 or so cities, towns, villages, and gores, and only 4 of these municipalities employ one or more municipal arborist. These communities are Burlington, Montpelier, Rutland, and South Burlington with a combined population of about 89,000 residents, leaving 511,000 Vermonters - roughly 93% of the population - living in communities that lack a dedicated tree expert on staff, instead relying on common sense to assess the risks associated with trees in their communities.

As outlined above, I am living proof that nonexperts can learn. You wouldn’t have wanted me in charge of assessing tree risk before I had even learned how to climb, but now I find myself, quite confidently, talking people off the ledge all the time to reduce the numbers of tree removals they are planning in their towns. I became more comfortable with trees in the landscape, and I hope you do too, as you check out these three keys to tree risk assessment that Vermont Communities can use to assess tree risk at a higher level.

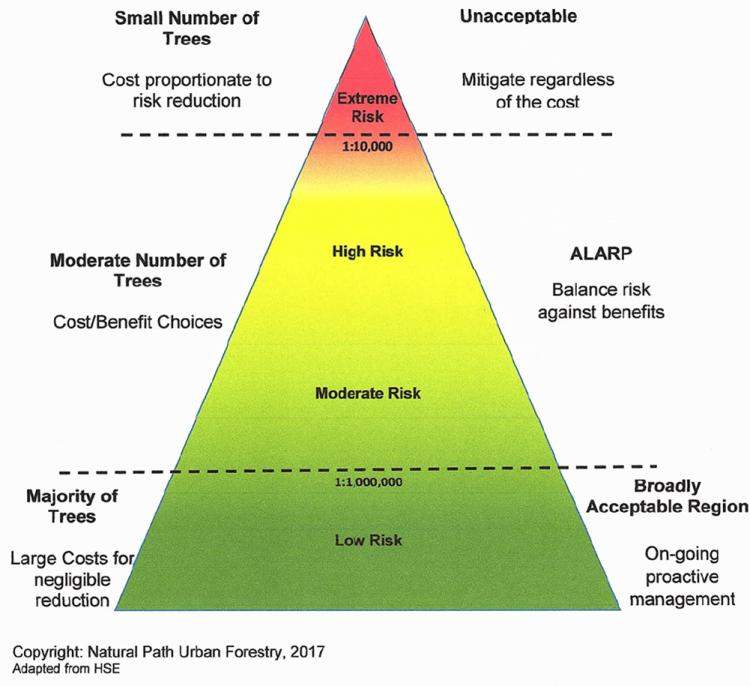

- Trees are Generally Low Risk: Trees, while they do pose some risk, are generally low-risk compared to other everyday hazards that we accept as a part of life. Over a 12-year period starting in 1995, an average of about 34 deaths per year were attributed to weather related tree failures in the US (Schmidlin, 2008). Compare that to numbers reported in recent years of other everyday activities like 44,000 traffic deaths. It is horrible when a tree failure takes a life, but thankfully it doesn’t happen often.

- Use a 1-year Timeframe: The chance of tree failure is 100% if you look at a long enough timeframe! However, viewing trees based on a possible event well outside our own lifetime is more cautious than necessary, and it ignores the fact that we will have many opportunities to act during that tree’s life if conditions change.

- Moving and Stationary Targets: In tree lingo, we call anything that we DON’T want a tree to land on a target. Compare these two targets in the drop zone of a dead tree: the road; and a pedestrian on the road. The road can withstand almost any tree impact without issue, while a struck pedestrian is a tragedy that we all want to prevent. The chances of this tree landing on the road are very high, no matter when the tree falls, but to hit a person, they must be there at exactly the wrong time, making these accidents exceptionally rare.

Tree Risk in Perspective

I think the numbers speak for themselves on this topic. In the US with a population of 345 million people, the odds of being one of the 34 Americans dying from a falling tree in a given year are .0000000985%. Or about 1 in 10 Million. An Australian study demonstrated that the likelihood of injury or death due to accidental tree failure is “very low”. There are other effects of tree breakage to consider, nowhere near as catastrophic as injury and fatality. There are road closures, power outages, property damage, cleanup costs, and other things which we want to avoid. Pretty much nothing we care about as human beings is improved by being struck by a tree, I will give you that.

But here is why I think tree risk is so low: tree failures tend to occur in bad weather, and bad weather tends to drive people to shelter. There are protective elements in our landscape that shield us from falling debris, so a tree or limb that lands on a house or car roof will hopefully stop before it hurts anyone. Even other trees can catch the falling wood before it reaches the ground. Also, tree failures are extremely point-specific incidents with a small area of impact. Imagine touching the trunk of a tree when it falls, you still won’t get hurt if the tree falls away from you.

Even though we can imagine the worst, that doesn’t mean it will happen. Realizing that trees pose so little risk allows us to think critically about it when someone calls the tree warden reporting a “hazard” tree or removals are proposed because trees are “dangerous.”

Using a Fair Timeframe

A one-year timeframe is specified by the International Society of Arboriculture’s Best Management Practices as taught within TRAQ. Assessing trees based on a longer timeframe is so uncertain that it’s unhelpful. We can’t make decisions for urban trees that extend much longer than one year because we can’t see the future. We don’t know if the tree will stop growing due to underground limitations, the building next to it gets demolished which removes the target of concern, or if it becomes adopted by a kindergarten class and named Princess Redleaf. We don’t know if pests will enter the area harming an adjacent tree species, making Princess Redleaf more essential than before and we don’t know if grant money will become available for rehabilitating urban trees that makes it feasible to improve the tree’s health with soil improvements, pruning or cabling. “Monitor” is the management option that is best suited for many urban trees over this shorter, more reasonable time frame. If concerning signs arise during the monitoring period you can always change your mind and take the tree down.

Another way that agencies and municipalities are using too long of a time frame with trees is when they assess maintenance costs and future growth conflicts related to trees. Every part of our infrastructure requires maintenance. We paint lines on the streets even though they only last a year with snow plowing and general wear. Signs need to be replaced when they are struck by vehicles or become so worn that they are hard to read. Bridges need to be painted and resurfaced regularly, and sidewalks need to be patched and replaced. The need for maintenance over the course of a tree’s life is not a fair reason to count it out of the landscape design. Removing trees to avoid maintenance costs is like locking a building to avoid sweeping the floor—you lose far more than you gain.

As noted above, less than 1% of Vermont’s municipalities have an arborist on payroll who has TRAQ. The reality is that determinations about tree care are made by volunteer tree wardens, local arborists stopping by to give an opinion, or tree boards who may or may not have any concrete experience or training. I think that looking at trees for a 1-year time frame would make ALL those types of tree assessors more accurate and reliable, just as it did for me. Adhering to this timeframe is a key difference between the Certified Arborist and the Certified Arborist with TRAQ.

When I was only a Certified Arborist, I did not think in these terms, and I tried to picture the tree’s entire lifespan like a timelapse animation before my eyes. It’s easy to imagine a tree falling eventually. They all do! But let’s take it one year at a time as the Best Management Practices tell us.

What is a Target?

If a tree falls in the forest and no one is there to hear it, does it pose a risk?

According to ISA guidelines, tree risk is the combination of the likelihood of failure (breakage), the likelihood of impacting a specific target, and the severity of the consequences of that impact if it occurs. The severity of an impact when a tree or limb falls on a person is very high. It’s easy to imagine the worst-case scenario and every one of us wants to prevent that from happening. But a limb landing on the sidewalk when no one is there, rather than being proof that the tree was a “hazard” all along, instead demonstrates that the likelihood of someone being hurt is quite low. The severity of a limb landing on a sidewalk is negligible. A guard rail. A kiosk. A bench. A granite monument. A fence. These things can be hit by falling limbs and trees, but once they are cleaned up, you may find there is no damage at all (I have inadvertently put this theory to the test with very mixed results). When this is the case, I tend to think of these targets as so robust that the consequence of a tree impacting it is negligible. After all, when I was city arborist of Montpelier, my only practical course of action in many cases was to climb a tree, clear the drop zone of people and property, then drop each tree part onto the pavement, dirt road, playing field, or walking trail below, deliberately directing each impact onto the hardened surface which I knew could take it.

So if these kinds of things are not high priority targets to manage for, then what are? Above all, people. Also animals, delicate or valuable property, power lines, and many other things, even other trees can be considered targets to protect, but what it comes down to is protecting people. No target, no risk. So its critical to assess what percentage of the day a person is in the drop zone of a defective tree. In Vermont, where our population density is low, its entirely possible that even in downtown areas, the occupancy rate of a person under a certain tree is below 25%, makes the target occupancy rate “rare” – the lowest category offered by TRAQ.

The Benefits of Trees

In conclusion, viewing trees solely as liabilities overlooks their significant benefits and the relative proportion of their risks. By understanding that tree risk is low compared to other risks we accept in our lives and by properly valuing the benefits they provide as urban infrastructure, we can make more informed, balanced decisions about urban forestry.

Keeping in mind the concept of the 1-year timeframe, the relatively low risk trees pose, and with an understanding that people are so mobile that they are unlikely to be under a tree at the time it falls, we can look at branches fallen on the road as a cleanup job instead of as a near miss.

Reading this article certainly doesn’t qualify a non-arborist to assess tree risk at the same standard as a trained professional, but it may have a similar effect that Klein (2023) observed, of causing Vermont’s tree managers from all walks of life to recommend fewer removals and more monitoring.

The following quote opened my eyes to the sunnier side of the tree risk coin. “The presence of risk is not intrinsically harmful: risk is simply a measurement of potential for deviation from an expected outcome, and the consequences of this deviation may be either good (resulting in opportunity) or bad (resulting in loss). The process of dealing with this uncertainty, and trying to achieve the best outcome in a changing environment, is the essence of risk management.” Reiss 2004.

Reiss makes the point that in addition to the benefits we know the urban forest infrastructure provides, maybe opportunities are cropping up in equal measure to the losses. What about when a car strikes a tree, but a pedestrian is protected behind the trunk? Or a kid gets excited enough about a certain tree that they spend their career working as an arborist? Or a traveler sees a double row of flowering crabapples lining a neighborhood street and in that moment they decide to make Vermont their new home? It’s important to manage risk, but let’s not forget that unexpected GOOD things happen too, especially when risk is managed wisely.

Written by VT UCF's Urban Forester, Adam McCullough, ISA Certified Arborist NE-7318A, TRAQ certified

Evaluating the Reproducibility of Tree Risk Assessment Ratings Across Commonly Used Methods 2023. Arboriculture and Urban Forestry. 2023. Ryan W. Klein, Andrew K. Koeser, Larsen McBride, Richard J. Hauer, Laura A. Warner, E. Thomas Smiley, Michael A. Munroe, and Chris Harchick

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/accidental-injury.htm accessed 9/18/2024

Reiss, C.L. 2004. Risk Management for Small Business. Public Entity Risk Institute, Fairfax, VA http://tap.pdc.org/TAPResources/RiskIdentification.pdf accessed 9/18/2024

https://injuryfacts.nsc.org/all-injuries/deaths-by-demographics/top-10-preventable-injuries/

https://www-fars.nhtsa.dot.gov/Main/index.aspx

Duntemann, M (2005) Elements of a Defensible Tree Risk Management Program. Natural Path Urban Forestry. www.naturalpathforestry.com

International Society of Arboriculture (2008) Municipal Specialist Certification Study Guide. Currid, P; Adams-Wiggs, L; Huntington L.; Picklesimer, P. www.isa-arbor.com

Schmidlin, Thomas W. (2008) Human fatalities from wind-related tree failures in the United States, 1995–2007. Article in Natural Hazards · July 2008